Welcome to the Stage Zero Information Hub

Deer Creek, Oregon courtesy Kate Meyer US Forest Service

Defining Stage Zero

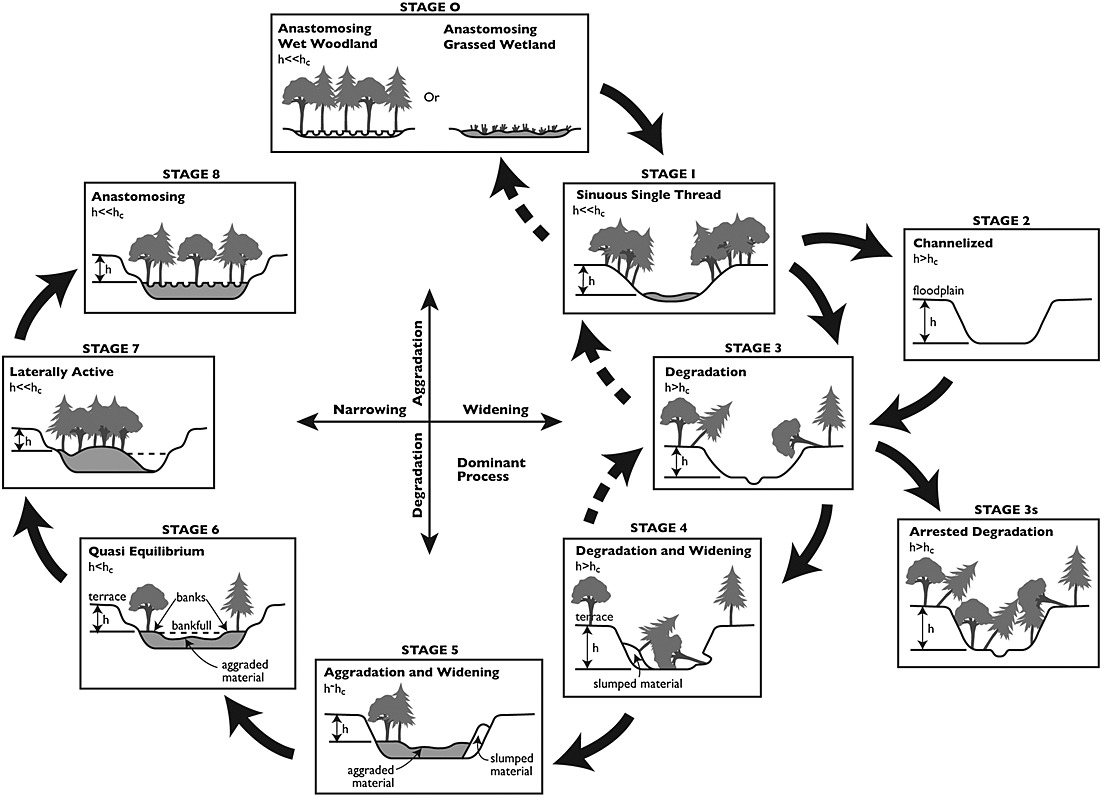

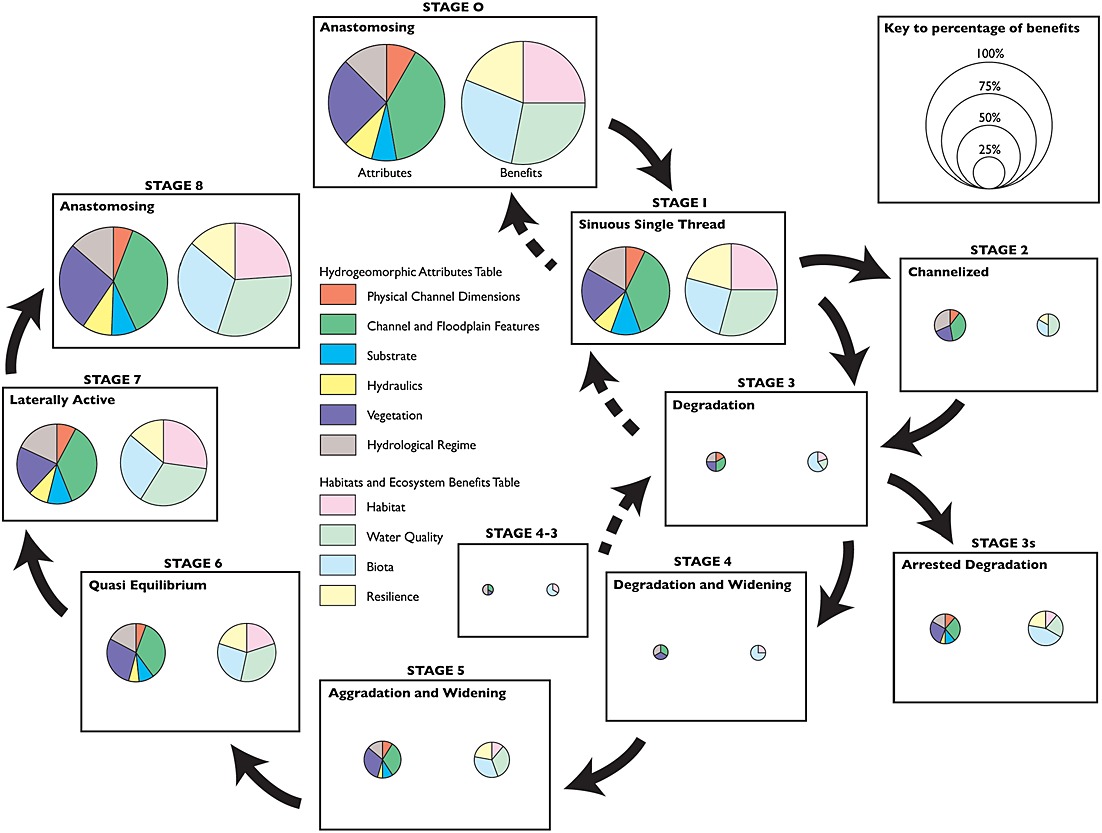

Stage Zero is the initial, pre-disturbance condition in the ‘Stream Evolution Model’ (SEM) proposed by Cluer and Thorne (2013). In the SEM, Stage Zero is characterised by an abundance of wide range of hydromorphic attributes and ecosystem benefits, high fluvial complexity, and full connectivity to the floodplain and the hyporheic aquifer.

‘Stream Evolution Model’ (SEM) proposed by Cluer and Thorne (2013)

click here for a full-sized version of these figures on the about page

Stage Zero is a condition in which an alluvial (self-formed) river and its floodplain have been undisturbed for a period of time sufficient to allow the cross-sectional geometry, planform pattern and long-stream profile to adjust to the catchment (watershed in US parlance) context, and prevailing flow, sediment, and biological processes.

In Stage Zero, the river characteristically comprises of a river-wetland corridor that may feature a patchy-wetland without a distinct channel, a multi-threaded planform (which may be braided, wandering, or anastomosed) or a single-threaded, meandering planform with side-channels.

The surface water component constitutes the stream and floodplain flows, which may be perennial, intermittent or ephemeral. The sub-surface component of the river (the ‘hyporheos’ – literally ‘the river below’) is fully-connected to the surface flows but may, or may not, be connected to the regional, groundwater aquifer.

When studying, describing and evaluating any alluvial river (but especially one that is in its Stage Zero condition), it is important to do so in three dimensions (long-stream, lateral (i.e. cross valley), and vertical), because a river is, by definition, “a system of inter-connected, surface and sub-surface flows that form a unitary whole”.

Brian Cluer and Colin Thorne, July 2021

The Long Road to Stage Zero River Restoration

Early efforts at stream restorations from the 1980s through the early 2000s by the US Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest, USA focused on channel-based and form-based methods to add needed habitat elements to degraded stream channels. While these efforts led to some local benefits in low gradient depositional environments, engineered solutions often failed during large storms, did not address key historic processes and rarely reconnected historic floodplains. Over time, Forest Service practitioners moved from channel-centric restoration to valley-wide treatments that focused on valley processes. This shift involved filling incised channels in unconfined alluvial valleys to create valley-wide connection. These reconnected floodplains in the Pacific Northwest, USA have increased habitat for threatened and endangered species of fish and wildlife, serve as foundational areas for food web and water table recovery and act as refugia during floods and fires. In response to Cluer and Thorne’s 2013 paper, Forest Service practitioners began referring to their projects as “Stage Zero Restoration”, and use of this ‘shorthand’ term for river-floodplain reconnection has now spread across North America and the UK.

Forest Service practitioners initially implemented Stage Zero Restoration on very low risk restorations of small, incised streams draining wet meadows on the arid east side of Oregon.

Restoration of a wet meadow to ‘Stage Zero’ by the US Forest Service practitioners. Left: pre-restoration (July) 2013, right one-year post-restoration. Red oval indicates the same tree stump, as a point of reference. Photo credits: Paul Powers

As the Forest Service personnel gained experience and confidence, they up-scaled Stage Zero river restorations to larger rivers on the wetter west side of the Cascade mountains, including the South Fork McKenzie River, where over 80 hectares of severely drained and degraded floodplain have been reconnected to te river, with plans to treat a further 160 hectares in the near future.

Restoration of the South Fork McKenzie River to ‘Stage Zero’ by the US Forest Service. Left: de-watered channel pre-restoration (aptly described as a ‘boulder ditch’), right: immediately post-restoration (2018). Photo credits: Kate Meyer and Johan Hogervorst.

Restoration to a Stage Zero condition can indeed be achieved by filling-in a degraded channel mechanically – which is sometimes termed a ‘valley floor reset’ and has been equated to pressing ‘Ctrl-Alt-Delete’ to clear an intractable computer problem. This approach is particularly apt if removal of redundant, artificial features such as levees and embankments can supply the sediment needed to fill the incised channel.

Stage 8 Restoration and process-based approaches

However, Stage Zero is a riverscape condition rather than a restoration outcome, nor a specific river restoration approach. Other approaches exist that attempt to invoke process (e.g. lateral migration and regrading the valley floor via bank erosion and redpositing of new floodplains). These include a number of different low-tech process-based restoration approahces (LTPBR) can be used to use promote processes that will nudge the system back towards a Stage Zero condition, often more incrementally. In less degraded systems, restoration to Stage Zero can sometimes be raipd with LTPBR approaches, especially when beaver can be reintroduced or allowed to re-colonise a river reach from which they were previously extirpated. Moreover, the 'valley floor reset' followed up with LTPBR can be used in conjunction with each other to harness natural processes and push towards Stage Zero or Eight.

Stage Zero can therefore be thought of as a destination rather than a journey. The path taken to restore a river to Stage Zero should be bespoke to the catchment context and anthropogenic setting of the river. In many locations, restoration of a river to its pre-disturbance condition may currently be impractical due to anthropogenic constraints. In these situations, it might be that "Stage Eight is great" (- See >Mark Beardsley's talk]) and anastamosing can be restored to something less than the full width of the valley bottom. But where a river can be fully reconnected to its former floodplain, this may represent the most sustainable, resilient future, with the greatest ecological uplift.

Johan Hogervorst, Paul Powers & Joe Wheaton, July 2021

Disclaimer

These statements express the opinions of the writers and do not necessarily represent the views of NOAA-Fisheries, or the US Forest Service.